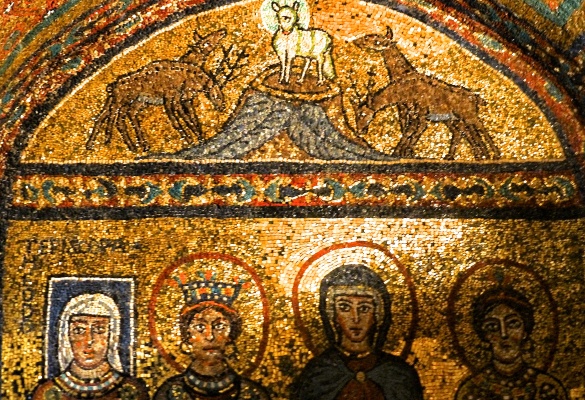

Yeah, that sounds a lot like a dissertation title, but the images of women in Roman mosaics from the second through ninth centuries in Rome, as well as art on early Christian sarcophagi suggest that the role of women in the early church was not that of second-class citizen.

Episcopa Theodora, Saint Praxedes, Mary the mother of Jesus, Saint Prudentia from the Chapel of Zeno, Church of Saint Praxedes, Rome

Paul the Apostle writes to the church in Rome, “I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon of the church at Cenchreae, so that you may welcome her in the Lord as is fitting for the saints, and help her in whatever she may require of you, for she has been a benefactor of many and of myself as well.”

Not only did some women in the early church have power (like the deacon Phoebe), but they some had wealth as well. What Paul is describing is a patron-client relationship, common throughout the ancient Mediterranean. Paul is the client and Phoebe is the patron (prostatis). It is worth noting that the Church of Rome today will not ordain women as priests or as deacons…and they wonder why the few priests willing to serve large parishes are worked to death. On a purely tactical level, if they opened the diaconate and the priesthood to women, they would effectively double their clergy pool! But, I digress.

Paul continues to write to the church in Rome, “Greet Prisca [a woman] and Aquila, who work with me in Christ Jesus and who risked their necks for my life, to whom not only I give thanks, but also all the churches of the Gentiles.” They were likely a married couple who did ministry together with Paul. Married? A woman in ministry?

“Greet Andronicus and Junia,” writes Paul about a man and a woman he describes as “my relatives who were in prison with me; they are prominent among the apostles.” Wait a minute…did Paul just call a woman a prominent apostle? Yes, he did.

All of those passages are at the end of Paul’s Letter to the Romans in chapter 16. In the “old” Revised Standard Edition, the editors used the masculine form of Junia’s name (Junias), because they found it inconceivable that the text provided the name a prominent female apostle. (Check any Greek New Testament, it says Junia.)

reading along the left margin (top to bottom): Theodora

reading along the top (left to right): Episcopa

The first thing I noticed about the four women depicted in the above mosaic was that one had a square nimbus…which means that she was still living at the time the mosaic was created. And she is the only one of the four identified by name: Theodora. And her title is Episcopa, the fem. version of the male noun Episcopos, which literally means over (epi-) seer (-scopos) and is what we translate into English as bishop. She was the mother of Pope Paschal I, who built the edifice and commissioned the murals in the 9th c. We don’t have records of who consecrated her as bishop…but if she was not a bishop, why label her as such…and with a nimbus to boot? Filial piety only goes so far. Some have written this off as a way to honor Theodora as the wife of a bishop. Huh? Why isn’t her husband depicted with a nimbus, alongside Saints Mary, Praxedes, and Prudentia? He’s not even there.

Praxedes (Prassede in Italian) was said to have died in 165 as a martyr (about 100 years after Paul was apparently martyred in Rome). She took care of those Christians who had been injured in the persecution and was entombed in the catacombs of St. Priscilla along with her sister, Prudentia. In the ninth century, her remains were removed and placed in the crypt of the church built in devotion to her by Pope Paschal.

In the above mosaic from the chancel of the church, she is shown with St. Paul as an equal. He has his arm around her shoulder in a very collegial manner. She is depicted as being as tall as he is and in a manner that conveys them as being of similar status. Interesting that they could pull this off in the 9th century. Did you see any women at the recent conclave that elected the pope…12 centuries later?

You may have heard a 2006 NPR report on a feminist pilgrimage that included the Church of St. Praxedes, reported by the inimitable Sylvia Poggioli. If you missed it, here is a link. (The one major omission of our pilgrimage was not inviting Sylvia Poggioli to dinner one night!)

From around 350, the inscription on this memorial mosaic reads, “Flavius Julius Julian, husband, to Simplicia Rustica, beloved wife, who lived 18 years, 5 months, and 15 days. She was my spouse for 3 years and and 2 months. May she rest in peace. She was buried January 23.” Her hands are raised in prayer.

And in the Pio Christiano Museum within the Vatican Museums, figures of a woman in prayer kept recurring among sarcophagi and in a stunning mosaic memorializing a young woman. Among the earliest Christian inscriptions is one of a woman named Petronia on the side of her marble sarcophagus. It shows her again in the position of prayer, which in the ancient world was emblematic of piety and faithfulness. And like the image of the man carrying a ram for sacrifice, it was used both in Christian and pagan depictions of piety.

We can’t know everything about the role of women in early Christian communities in Rome, but indications point not simply to their presence, but to their leadership. The church today is losing out on the gifts of women for ministry every time we act or even think that women should play anything but an equal role in clergy leadership. You wouldn’t think this would still be an issue…but it is for Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, fundamentalist and some evangelical Christians. All I can say is look to our past and look to your future.

Pingback: Gender, by God | Reflections of God's Love